Detecting Emotions from Voice with Very Few Training Data

Full paper available on arXiv.

Speech emotion recognition has become more and more popular over recent years, largely because of the large range of applications enabled by the technology in fields ranging from human-computer interaction to healthcare. Tech giants have also seen this future potential and have been launching new products such as the Amazon Halo which can detect emotions in real-time from the voice. However, there are still some challenges that need to be surpassed to unleash the full potential of Emotion AI.

Recently, I’ve been collaborating with WonderTech, a leader in Emotion AI, to improve emotion recognition in situations where training data is scarce. Long story short, we obtained very competitive performance with a little more than 100 training examples per emotion (each example is ~5 seconds). Our model was able to perform well thanks to the use of pre-trained representations, extracted from Facebook AI’s wav2vec model.

Challenges

There are many challenges to accurate emotion recognition like dealing with noise, but the most important ones are the lack of labeled data and the fact that we still don’t know which features are the most suitable for the task.

Lack of labeled data

A big hurdle for emotion detection is the lack of available data. For example IEMOCAP, the most popular benchmark dataset for speech emotion recognition, only contains 8 hours of labeled data. Compare that to the large datasets available for Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR), where modern systems are trained on more than 10,000 hours of data.

There are also other data challenges in these datasets, such as an uneven number of classes, diversity issues with a few speakers or few different domains, “acted” speech vs “natural” speech…

Choice of features

Researchers have been experimenting with many different features to understand which ones contain the most salient emotion signal. However, it is still unclear which ones are the most suitable. Here is a quick overview of what’s currently out there.

Low-level descriptors

These are hand-engineered features that were found to work well in other speech-related tasks such as automatic speech recognition or speaker identification. They are usually computed on short time frames of speech of around 20-50 milliseconds. There exist hundreds of such features related to various aspects of the audio signal such as energy or pitch.

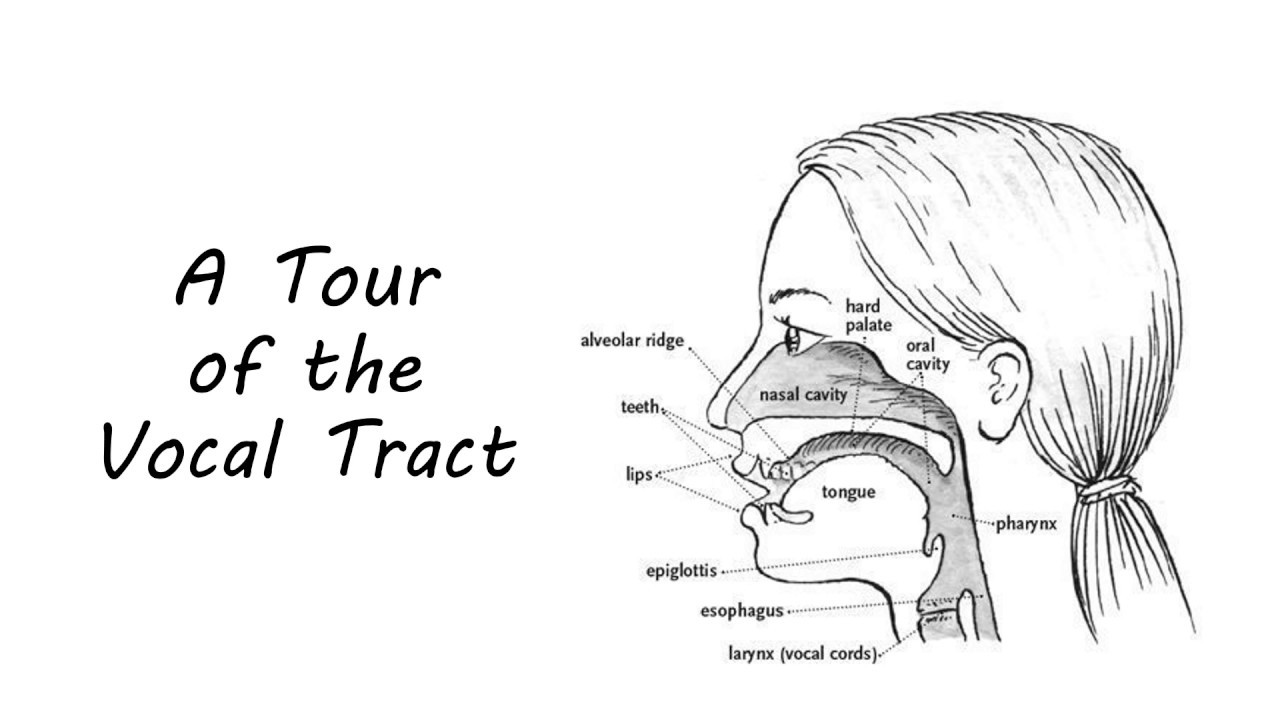

The most popular are MFCCs or Mel-Frequency Cepstrum Coefficients. These coefficients are computed in a way that is able to represent the shape of a person’s vocal tract speaking.

While MFCCs and other low-level descriptors work reasonably well, critics point out that such features are often too simple and can lose many important information from the original signal.

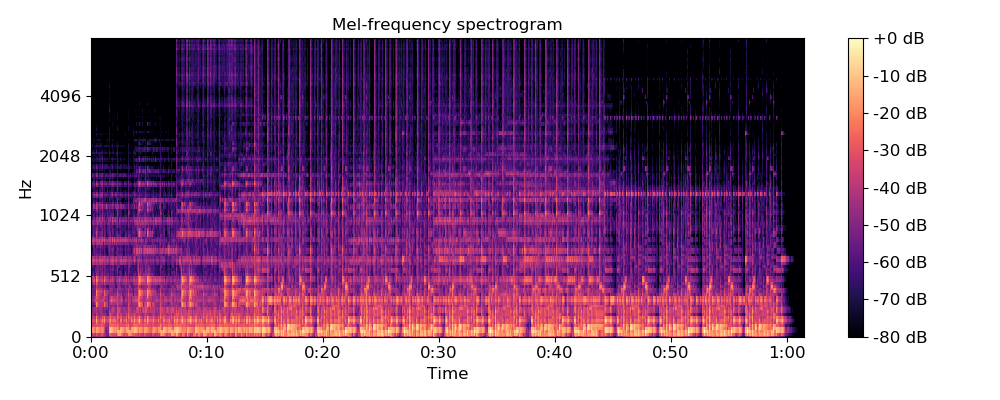

Spectrogram and filter banks

Another approach is to use the variation of the audio signal frequencies across time. Proponents of this approach argue that such features are more natural, flexible, and less opinionated than the manually crafted features above. Indeed, most low-level descriptors are computed after first extracting frequency information from the audio signal, including MFCCs. By feeding the model with a more “pure” representation of the signal, we can let the model learn the best features by itself without influencing it with potentially biased human prior.

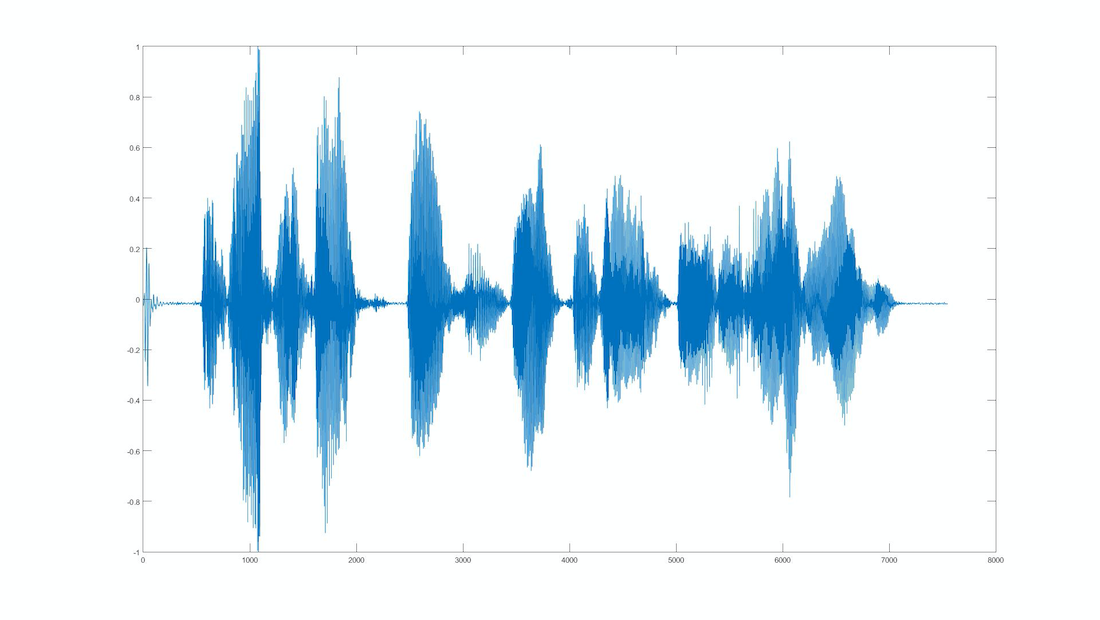

Raw audio

Yet, even spectrograms are an imperfect representation of the “raw signal”. There are still the result of a mathematical transformation that loses some information from the source. This is why using the raw audio signal is theoretically the best approach if we want to give the model complete freedom in identifying the best features by itself. This idea is in line with other domains of machine learning such as vision or natural language processing, where the most performant models are deep ones trained directly on the raw input.

This approach has been proven to work well, as demonstrated by DeepMind’s WaveNet or Facebook’s wav2letter. However, the model needs to be much deeper in order to be able to detect meaningful patterns across the raw signal. And to train a deeper model we need… more data! We are back to our first problem of small labeled datasets.

Transfer learning to the rescue

Over the past decade, great progress has been made in other domains like NLP or computer vision. A big part of it is due to the rise of transfer learning, which transfers knowledge gained from one bigger dataset (usually for a more general task) to a target dataset.

In computer vision, it is now standard to re-use a model pre-trained on the large ImageNet dataset before fine-tuning it on a smaller dataset for the target task.

In natural language processing, large pre-trained models like BERT or GPT are now being fine-tuned on a multitude of tasks and perform much better than other approaches.

Surprisingly, however, transfer learning has not taken off for speech yet, mainly because it is still unclear which task is the most suitable for pretraining.

Learning unsupervised representations with wav2vec

Wav2vec is a recent model released by Facebook in 2019. It was inspired by word2vec, a now very popular technique to learn meaningful embeddings (vectors) from raw textual data. Similarly, wav2vec was trained on unlabeled speech data, meaning that only the raw audio signal (no transcriptions) was used during training. This is a potential game-changer for speech applications as the model can be trained on any language or domain without needing to spend time and resources labeling the data.

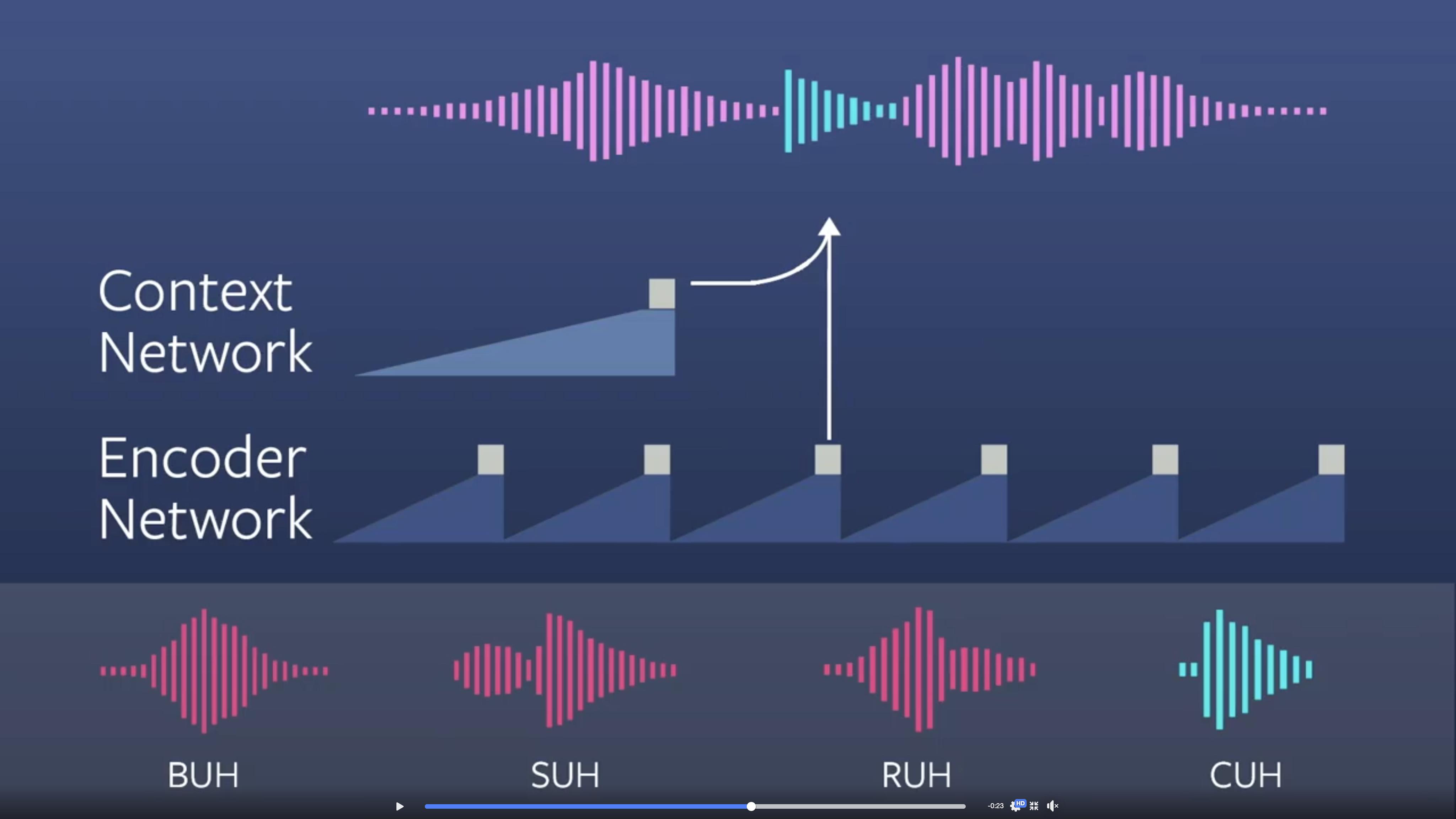

The model consists of two convolutional networks stacked on top of each other: the encoder network and the context network. While the encoder can attend to only ~30 milliseconds of speech, the context network can combine multiple encoder outputs to model around 1 second of raw audio. The model then uses this contextual representation to predict what comes next. More specifically, it learns to distinguish between real future 10ms samples and distractor samples that were taken randomly from other sections of the clip.

Wav2vec uses contextual representations to distinguish between real and fake future samples of audio. Here “CUH” is the correct sample.

After training wav2vec on 1,000 hours of unlabelled data, Facebook then used the learned contextual representations to train an independent ASR model, replacing the previous spectrogram features. This resulted in 22 percent accuracy improvement over Deep Speech 2, the best system at the time while using two orders of magnitude less labeled data.

Using wav2vec representations to recognize emotions

Although wav2vec was made in the objective of Automatic Speech Recognition, we wanted to know if the contextual representations also contained emotional content. We decided to feed wav2vec’s contextual representations in a variety of classification models and to compare performance with traditional features like low-level descriptors or log-Mel spectrograms.

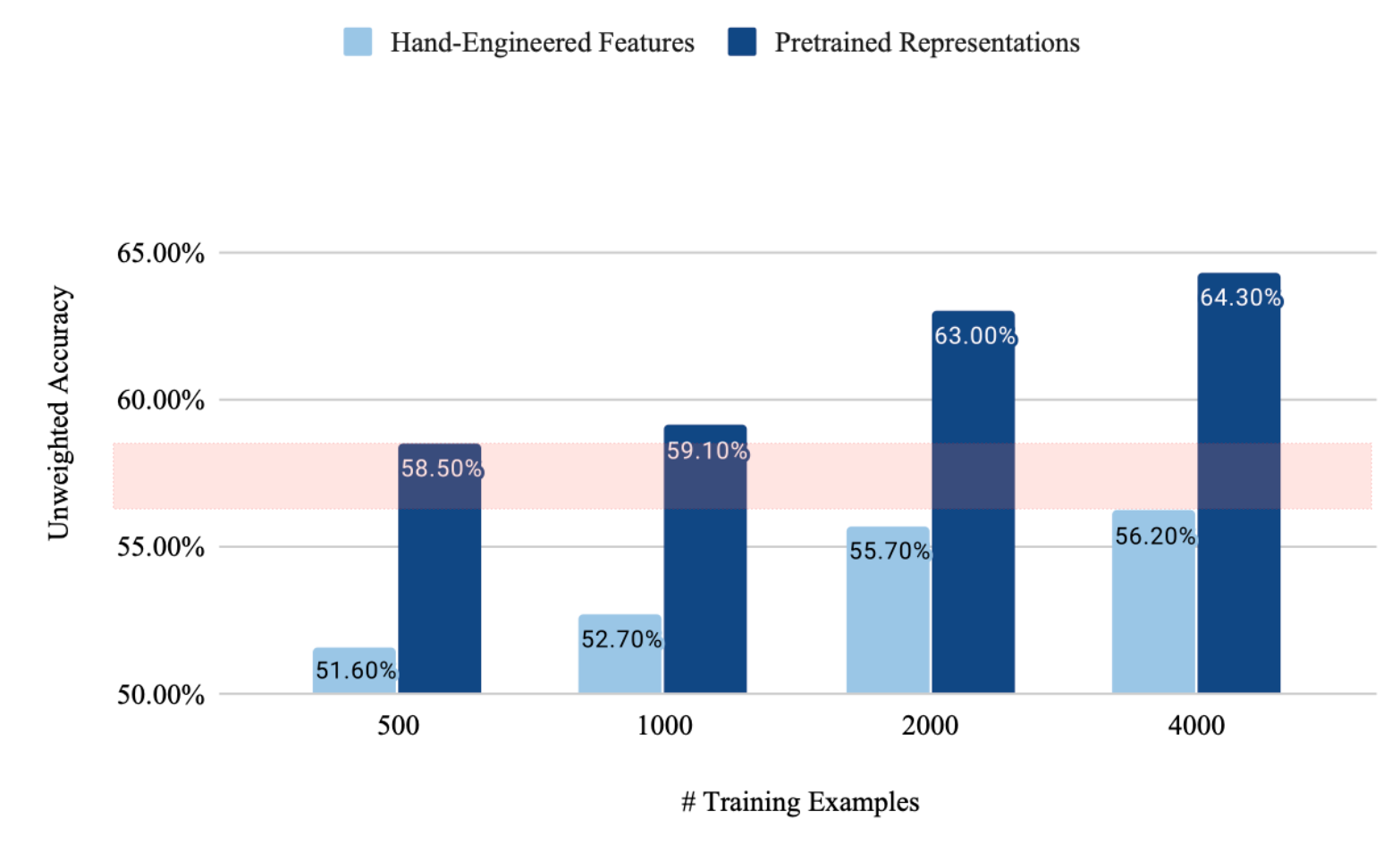

We trained our models on the IEMOCAP dataset, the most popular benchmark for speech emotion recognition. The results were conclusive, with the contextual representations performing much better than any other feature set that we experimented with. We were able to get better performance than with hand-crafted features with 8 times less data! This indicates that wav2vec is indeed capable of learning emotional information by itself without explicitly told so (remember, the training objective was only to distinguish true future samples from fake ones).

Combining speech with linguistic features

In one last experiment, we decided to combine the wav2vec representations with textual representations to provide our model with extra information about the linguistic content of speech. We decided to encode the text transcriptions of each IEMOCAP dialog using BERT, another model often used for transfer learning in NLP. When combining audio and text, an important challenge is the one of alignment. For example, how can the model learn which segment of audio corresponds to a given word?

To answer this, we built a multimodal model using attention to align the speech representations (wav2vec) with textual representations (BERT) along the time dimension. When cross-validating our multimodal model on the 5 sessions of the IEMOCAP dataset, we were able to reach an unweighted accuracy of 73.9%, more than all the other multimodal techniques that we reviewed.

Conclusion

Our research clearly shows the potential of transfer learning for emotion recognition. The re-use of unsupervised representation allows for accurate models even when training data is scarce. Still, enough labeled data will be needed to reach optimal performance and mitigate risk in sensitive applications such as mental health. Data diversity is especially important to allow models to work for any person speaking, no matter the language, dialect, accent, gender, or age.

The research in transfer learning and self-supervised learning for speech applications is also moving fast. Since the original version of wav2vec, Facebook has been releasing two subsequent iterations of the model: vq-wav2vec and wav2vec 2.0, the latter inspired by the masked language modeling objective function of BERT.

For more details about our methodology and model, you can go here to read our full research paper.